How Fast Does Chronic Kidney Disease Progress?

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) doesn’t progress at the same rate for all patients. A significant portion of patients with mild-to-moderate CKD do not experience a predictable pattern of disease progression.

Extensive research has uncovered several indicators that influence the speed of CKD progression, including whether or not the disease progresses at all. Factors like genetics, underlying health issues, age, sex, and lifestyle choices, however, can also affect a study’s findings and alter the outcome.

While this can make the question “How fast does chronic kidney disease progress?” a tricky one to answer, here’s a breakdown of what scientists and medical professionals know about kidney disease progression up to this point.

How long does CKD take to progress?

The short, and unsatisfying, answer to this question is…it depends. It can be difficult to determine which indicators will be accurate across the board because individual studies can only examine a certain number of factors at one time. They also generally look at very specific combinations. Collectively, however, these studies provide small pieces that help fill out the larger picture over time.

Chronic kidney disease progression has been studied extensively, but the majority of studies have focused on the causes of kidney function decline and the likelihood of CKD to progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD)—not necessarily the speed of that progression.

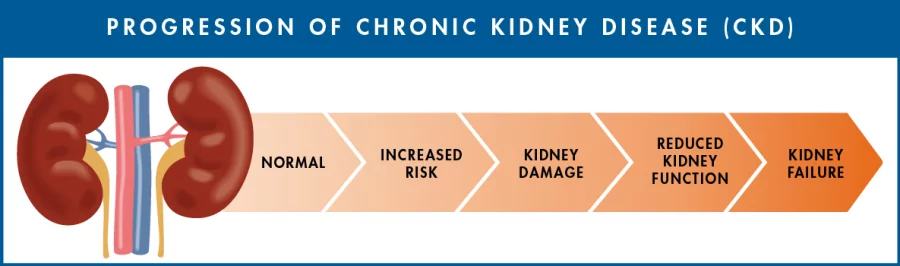

This infographic is by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The goal of accurately, consistently predicting the speed of chronic kidney disease progression remains at the forefront of CKD research. Findings show that the rate is influenced by many factors and can vary widely, particularly in later stages of the disease.

What are some indicators of fast kidney disease progression?

While the rate of disease progression will be different for everyone, multiple studies have shown that reliable indicators of faster progression include:

- Hypertension (high systolic blood pressure)

- Proteinuria (higher than normal amounts of protein in urine)

- Congestive heart failure (and previous cardiovascular disease)

- Anemia (insufficient oxygen-carrying red blood cells)

- Low serum albumin (low levels of the protein albumin in the blood)

- Age of under 65, especially if diabetic

- Longer duration of diabetes before diagnosis

- African, Caribbean, Bangladeshi, Native American, or Pacific Islander ethnicity

Additional factors that various studies have shown to indicate a faster progression of CKD include:

- Acute kidney injury (AKI)

- Being a current smoker

- Of the male sex

- Treatment with dual RAS blockades

- Low hemoglobin levels (<13 g/dL)

Why is determining the speed of CKD progression important?

As the above studies show, there is a myriad of factors that can contribute to how fast chronic kidney disease progresses. This is complicated by the influence that genetics, related medical conditions, age, sex, lifestyle, and other various health aspects can have on a study’s findings. As a result, our knowledge of the disease and our ability to make accurate predictions about its trajectory remains imperfect, despite continued progress.

Are there any proven ways to slow disease progression?

Research has taught us that there are steps we can take to slow CKD progression and protect your kidneys. While they are particularly effective when implemented in the early stages, they’re helpful no matter what stage of the disease you’re in, as well as preventative measures.

Make healthy lifestyle choices

- Eat a diet that:

- is high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains;

- is low in cholesterol, saturated fats, sugar, and preservatives;

- limits sodium to 2,300 mg/day, to help control blood pressure;

- includes adequate, not excessive, protein; and

- is low in potassium and phosphorus.

- Quit smoking, and don’t start if you are not a smoker.

- Exercise regularly and frequently, at least 30 minutes a day five days a week.

Stay ahead of your CKD

Responsum for CKD empowers people with kidney disease through community, knowledge, and shared experiences

Talk to your doctor and follow your treatment plan accordingly

- Ask your doctor what amount of daily fluid intake is safe for you, and make sure to count all liquids in your fluid intake, not just water, and limit alcohol and caffeine consumption.

- Monitor and manage underlying health issues that could increase your risk for complications and fast disease progression, including:

- Diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes)

- Hypertension

- Heart disease

- Anemia

- Take your medications and alter your lifestyle habits according to your doctor’s instructions.

- Limit your use of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve).

What does research about kidney disease progression show?

Beyond the above findings, research shows additional indicators, which can, at times, seem contradictory. The following studies provide insight into additional factors that contribute to fast CKD progression and present the challenges of determining an accurate timeline for all patients.

Multiple studies have been performed to find potential indicators of faster disease progression for CKD. (This design was created by @katemangostar for Freepik)

BMJ Open study

Published in 2017, this study examined ethnic differences in CKD progression and the risk of death in adults with diabetes. The study found the following indicators of faster progression:

- Diabetics under the age of 65

- Bangladeshi, African, and Caribbean ethnicity

- Hypertension, proteinuria, cardiovascular disease, and longer duration of diabetes

Additionally, the odds of a rapid eGFR decline doubled for participants ages 25-54 and significantly increased (by 38%) for those ages 55-64.

Clinical Kidney Journal study

This 2018 study looked at scatterplot patterns of CKD progression in its later stages. At the 16-month follow-up, 583 participants (64%) had begun dialysis, and 142 participants (16%) died before dialysis was initiated.

Of those who had begun dialysis, the participants who required earlier initiation were:

- Young

- Male

- Treated more frequently with a dual blockade of RAS and/or beta blockers

They also had at baseline (information or value that’s taken at the start of the study):

- Lower kidney function

- Higher systolic blood pressure

- Proteinuric renal disease

Patients who died before dialysis were older current smokers, had proteinuric renal disease, and had high degrees of related medical conditions. They were, however, treated less frequently with heart medications, called ACEIs (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) and ARBs (angiotensin II receptor blockers). This suggests that treatment with ACEIs and ARBs make death less likely, but kidney failure more likely.

This same study found that discontinuing certain medications commonly prescribed for CKD patients was associated with slower progression. These drugs included:

- Vitamin D analogs (increase vitamin D levels and helps the body absorb calcium)

- Fibrates (lower blood triglycerides, often prescribed for people who can’t take statins)

- Allopurinol (treats gout and lowers uric acid levels increased by kidney stones)

All three of these are suspected of contributing to kidney function decline.

BMC Nephrology study

Also published in 2018, this study explored the different rates of CKD progression in adult participants with and without diabetes. Out of 36,195 adults with CKD stage 3 (eGFR 30-59), with a mean age of 73 years, fast progression occurred for 23.0% of participants with diabetes vs. 15.3% of those without.

The fast progressors with diabetes were either 80 years or older or between the ages of 18 and 49. They all had anemia, heart failure, high systolic blood pressure, and proteinuria. Regardless of diabetes status, the strongest independent predictors of fast CKD progression included being age 80 or older and having proteinuria, elevated mean systolic blood pressure, heart failure, and/or anemia.

Fast progressors were more likely to have:

- Prior cardiovascular diseases (acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, heart failure, atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, and/or pacemaker)

- Prior ischemic stroke and/or transient ischemic attack

- Peripheral artery disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Dementia

- Dyslipidemia (unbalanced levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood)

- Chronic liver disease

- Thyroid disease

They were also more likely to be receiving one or more of the following medications:

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Loop diuretics (used to treat hypertension and edema due to CHF or CKD)

- Beta blockers

- Calcium channel blockers (used to lower blood pressure)

- Alpha blockers (used to lower blood pressure, and ease urination for men with enlarged prostates)

- Aldosterone receptor antagonists

- Isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine (used to treat coronary artery disease and heart failure)

- Antiarrhythmic medications

- Nitrates

- Statins

- Other lipid-lowering therapies

- Antiplatelet agents

- Diabetic therapy

- Erythropoietin

In patients without type 2 diabetes at baseline, predictors of fast CKD progression included:

- Age ≥ 70 years

- Heart failure

- Prior ischemic stroke

- Prior pacemaker implantation

- Proteinuria

- Higher entry-level of eGFR

- Lower hemoglobin levels

- Low HDL cholesterol (< 50 mg/dL)

- Current or former cigarette smoker

In patients without diabetes, individuals aged 50-69 were less likely than those aged 70-79 to have fast CKD progression. In participants with mild-to-moderate CKD, accelerated decline in kidney function affected approximately one in four (1 in 4) with diabetes and about one in seven (1 in 7) without diabetes.